When IVF patients have mosaic embryos, how should they decide whether to transfer, store, or discard them?

When a patient goes through in vitro fertilization (IVF) and opts to have preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A), it can be disheartening to find out that some or all of their embryos are mosaic.

Before we go into detail about mosaic embryos, however, let me first mention that the goal of doing PGT-A is to identify some euploid embryos. Euploid embryos contain the expected complement of 46 chromosomes in each cell, and are the ones fertility clinics intend to transfer during an IVF cycle. Why? They are more likely than mosaic embryos to implant and lead to a healthy pregnancy.

Now let’s address mosaic embryos. Mosaic embryos contain a mixture of cells; some are chromosomally normal, and some are chromosomally abnormal. The atypical embryonic cells are also referred to as aneuploid, which is why the testing is referred to as preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy.

(Seeking more information about PGT-A? Then check out this link.)

Image credit: https://www.focusonreproduction.eu/article/News-in-Reproduction-PGTA

A changing landscape

There is a lot of controversy over transferring embryos identified as mosaic by PGT-A, and some clinics will not transfer them because of the possibility that the mosaic embryo could result in a baby with mosaicism. However, some clinics will now transfer them, and these days we also know that mosaic embryos may self-correct! This means that over time, an embryo that’s classified as mosaic may become euploid. Fascinating, right? There are several theories about how this happens, but one theory is that the aneuploid cells are more likely to die or grow at a slower rate as compared to the euploid cells. Perhaps this process of self-correction is actually a common phenomenon, but we just didn’t know it because we weren’t testing embryos as frequently as we are today and the earlier technologies were less sensitive.

And speaking of sensitivity, the newest technology used to carry out PGT-A is called Next Generation Sequencing (NGS). It is reported to be more sensitive than the older technologies and finds a higher number of tested embryos to be mosaic as compared to previous methods. So as we continue to use this more sensitive testing, it is possible that more IVF patients will find themselves in the situation where they only have mosaic embryos to choose from, or they don’t have enough euploid embryos to create the family they desire. How do they decide whether to transfer their mosaic embryos, freeze them for potential future use, or discard them because they are too risky to transfer?

A ranking system to help prioritize mosaic embryos

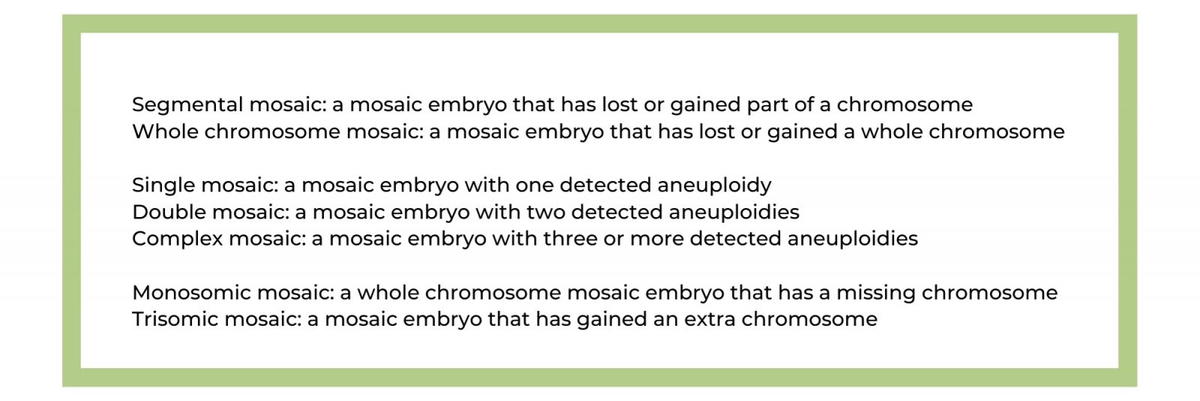

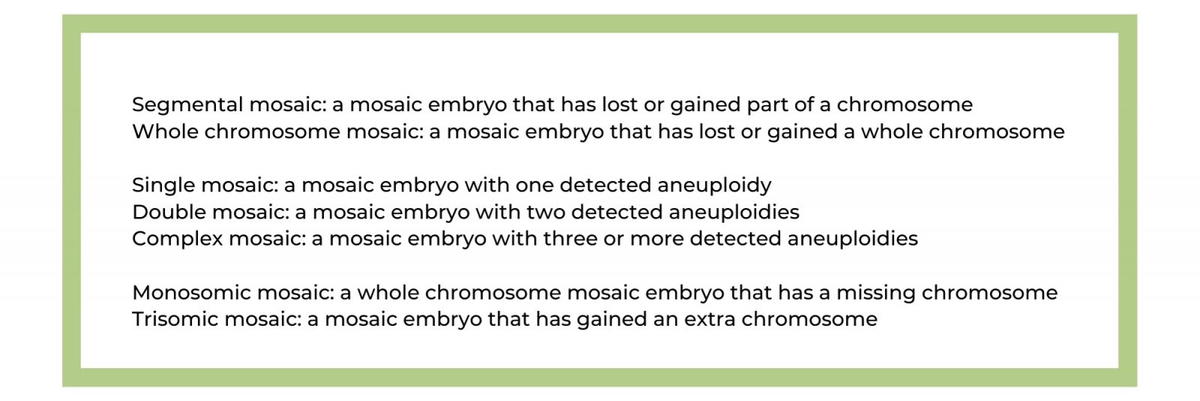

A recent paper (Mourad et al., 2021) identifies different categories of mosaic embryos and provides a ranking system, where some categories are preferred over others. The authors examined the rates of “ongoing pregnancy or live birth” and the rates of miscarriage for each type of mosaic embryo that was transferred. If a certain type resulted in a higher rate of ongoing pregnancy/live birth and a lower rate of miscarriage, it was considered preferential for transfer. Here is what the authors found:

- Segmental mosaics should be prioritized over whole chromosome mosaics.

- Single or double mosaics should be prioritized over complex mosaics.

- Embryos that show aneuploidy in <50% of the cells should be prioritized over those with aneuploidy in >50% of the cells.

- There was no preference found for monosomic mosaics as compared to trisomic mosaics.

(Seeking more information about different types of chromosome abnormalities? Check here!)

It is important to note that there is only one case reported in the literature of a child being born with mosaicism after a mosaic embryo was transferred. The current belief is that if mosaicism interferes significantly with embryonic development, the embryo will likely not implant in the uterus or it could implant but then the patient will miscarry. So one could argue that we should be more accepting of mosaic embryo transfer (MET), as long as the patient is willing to accept the risk of miscarriage. That said, we have caution in that sometimes children ARE born with mosaic chromosome problems, and mosaicism can impact lives. The "red flag" posed by the mosaic embryo test result suggests that we might classify these embryos differently in terms of risk and transfer priority.

Other considerations - we need to pay attention to the affected chromosome(s) and the testing method used

This ranking scheme should NOT be the sole factor used in assessing whether an embryo should be considered for transfer. The affected chromosome (or chromosomes) matter too, and there are also various chromosomal scoring systems that already exist.

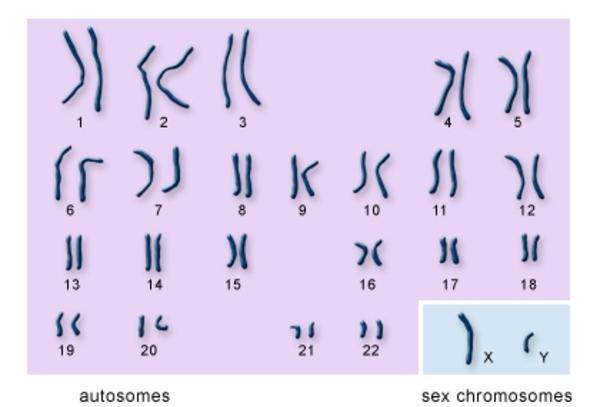

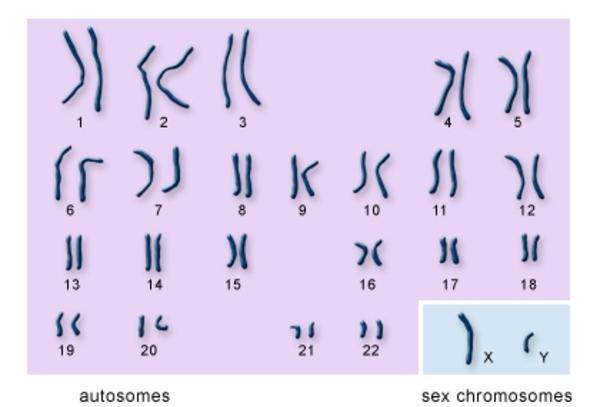

You may know that the typical human cell has 23 pairs of chromosomes of varying sizes that make for 46 total chromosomes, as shown in the image below. With the exception of the “sex chromosomes” that determine the sex of the fetus, the chromosomes are referred to by number.

Image credit: U.S. National Library of Medicine

For example, according to this chromosomal scoring system, if a mosaic embryo has an extra chromosome “1” in 40% of its cells, that is preferable for transfer when compared to a mosaic embryo that has an extra chromosome “18” in 40% of its cells. This chromosomal scoring system was developed by looking at whether “adverse outcomes” occur when there is an aneuploidy for a specific chromosome number. Examples of adverse outcomes are miscarriage or a child being born with special medical needs or intellectual disability. The big takeaway here is that when deciding whether to transfer a mosaic embryo, it is important to consider both the type of mosaic embryo AND the affected chromosome(s).

Different labs use different technologies and different percentage “cutoffs” when reporting whether a mosaic embryo is considered to have a “high” or “low” percentage of aneuploid cells. The conclusion by Mourad et al. that an embryo is preferred for transfer if <50% of its cells are aneuploid only applies when the lab used a 50% cutoff and Next Generation Sequencing to carry out PGT-A. To determine whether the rankings put forth by Mourad et al. are relevant in analyzing one’s mosaic embryos, it is important to know what testing method was used.

A patient’s testing report may mention both the cutoff and the technology used for PGT-A, but it is also possible to request this information by asking to speak with a genetic counselor at the lab. Additionally, you might find some reassurance in speaking to an independent genetic counselor, where you can spend the time considering all the factors that might go into a transfer decision.

The ranking system presented by Mourad et al. may be able to help fertility patients prioritize some mosaic embryos over others if they only have mosaic embryos available for transfer. This paper provides a taste of the literature that genetic counselors in the fertility space consider on a daily basis. Anyone who is considering how to handle their mosaic embryos should seek advice from a genetic counselor who is committed to staying current with the ever-evolving pipeline of new information. Genetic counselors specialize in helping each patient make sense of the data, the specific risks that might be present for their embryo(s), their feelings about other testing options or fertility options that are on the table for them. After consideration of all these factors, the patient should be in a position to make a decision that feels right to them. If you need a genetic counselor in your corner, consider Advocate Genetics!

Disclaimer: Please keep in mind that the information provided here is not meant to be a medical opinion about your specific case. The problems of every patient are unique and should be addressed by their physician or other health-care professionals in an individual conversation. You are welcome to bring up questions inspired by this blog post with your medical team. However, no one should use this blog as a source of medical care.